Holocaust Remembrance Day

Yom HaShoah or Holocaust Remembrance Day, as it is observed in Israel, this year begins on the evening of May 4th and ends on the evening of May 5th. I’m not Jewish, but I am choosing to commemorate it on my site this year because it’s always good to be reminded of history and how easy it is to flirt with darkness and get drawn in. For me, World War II is not a remote history lesson, something I learned sitting in school or watching the History channel, but a gritty, visceral reality—I spent many hours with Julian Moody, a real World War II veteran, as he shared his experiences and showed me the many photographs he took during his service. I could see that Julian was deeply affected by the war and it was still with him after many decades. The word he used often to describe it was “epic” and I definitely had the sense of huge forces of world history playing themselves out on a grand scale, and his participation in this was not something to take lightly. No, we may never have a literal Holocaust of the type in World War II in America, but the root of evil can take many forms—the hatred, fear, and intolerance that lurks beneath the veneer of any civilization along with any sociopathic tendencies in a leader can quickly metastasize into senseless chaos and destruction that is hard to stop once it is fed by public hysteria and gains momentum, as was painfully learned in World War II.

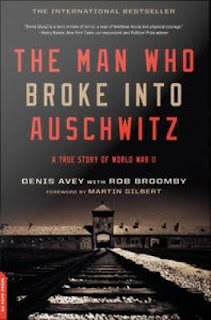

I have been blessed to come across two striking first person, nonfiction accounts of that era: Diary of a Man in Despair by Friedrich Reck and The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz: A True Story of World War II by Denis Avey. I would recommend the books to anyone interested in learning more about that dark period in our history. I read the books last year since 2015 marked the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and even though that was many months ago, I thought back to the books often. The quality of writing in both books is especially notable, and the insights gleaned also serve as a warning on the current political climate.

Diary of a Man in Despair by Friedrich Reck is an unusual document, unlike anything I’ve read in a long time. Reck was a non-Jewish German man who moved in higher social circles and could have belonged to the Nazi party but was repelled by it. His Diary is not a literal diary of dated daily entries, but rather thoughts, reflections, and observations written in the years 1936 to 1944 as he watched his country fall into the abyss. His writing was very critical of Germany and the Nazi regime so he wrote at tremendous risk to himself. In spite of warnings by friends (an acquaintance of theirs was raided by the Gestapo) he persisted in his writing, hiding the pages in a tin box which he buried in the woods on his extensive property. Only in the final weeks of the war, were the pages removed from their hiding place. They were first published in Germany in 1947 by a publisher who soon went out of business, but reprinted in 1964 and 1966, with an excellent English translation in 1970 by Paul Rubens. At the time Diary was first published it received little attention and Reck was (and still is) misunderstood and dismissed by some as an annoying aristocrat whining endlessly about the cow-like stupidity of “mass-man,” which is unfortunate. Diary is full of keen insights, along with unique, close-up observations of Hitler since they ran in the same social circles. Reck’s description of his first close up encounters with Hitler who was not yet a major political figure runs as follows:

Much later, at a public rally, in examining Hitler’s face through a pair of binoculars, Reck noted, “the face bore the stigma of sexual inadequacy, of the rancour of a half-man who had turned his fury at his impotence into brutalising others.” which is remarkable considering in recent years there has been some speculation, based on a doctor’s report, on Hitler suffering from a genital deformity. In reflecting on his impressions of Hitler over the years, Reck writes, “Notwithstanding his meteoric rise, there is absolutely nothing that has happened in the twenty years since I first saw him to make me change my first view of him. The fact remains that he was, and is, without the slightest self-awareness and pleasure in himself, that he basically hates himself, and that his opportunism, his immeasurable need for recognition, and his now-apocalyptic vanity are all based on one thing—a consuming drive to drown out the pain in his psyche, the trauma of a monstrosity.”

Reck also gives cutting observations on the social and economic forces in Germany that gave rise to Hitler and the Nazi war machinery. Hitler’s self-hatred and monomaniacal need for power coincided with a turbulent political and economic situation that had roots in previous regimes as well as the stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression. Add to this mix the German government’s increasing collusion with corporations and the relentless drive towards industrialization. Reck viewed the German fixation with mercantilism, industrialization, and technology as vulgar and barbaric, the mindset and mentality epitomized in what he derisively termed “mass-man”. Reck saw “mass-man” as spiritually bankrupt and ultimately spawned from the shadow side of the French Revolution which famously made Reason into a cult and germinated the concept and fervent hysteria of Nationalism “which puts an aura of heroism around mercantilism and the bourgeois drive for power…” In writing of this mass mentality that had become entrenched in Germany, Reck writes, “It was possible only at a time of generalised atheism, and purposelessness, and brute force. Of course, I.G. Farben welcomed Hitler—he provided their poison factory with the aura of a philosophy!” As if to validate the popular adage that Satan most successfully deceives by making people believe he (and God) doesn’t exist, in despair Reck writes, “My life is loneliness, and the growing awareness that it must be so—loneliness among a people whom Satan has overcome, and the awareness that only by suffering can the future be changed…” Reck further notes that Germany, in such a spiritually bankrupt atmosphere, gave license to its worst side: “every nation normally puts its demons, its delusions, its impossible desires away into the cellars and vaults and underground prisons of its unconscious; the Germans have reversed the process, and have let them loose.” As we all know, all these forces and elements plaguing German society came together as in a perfect storm culminating in the Nazi military industrial complex and a military campaign bent on taking over all of Europe as well as its most evil manifestation—industrialized murder.

The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz, written by Denis Avey (with Rob Broomby), gives an excellent account of World War II from someone who served as a British soldier. Avey was just one year and four months younger than my American veteran friend Julian, so it was interesting to get a different and British perspective of the same war from someone around the same age as Julian. Avey was born on January 11, 1919 and grew up in the village of North Weald in Essex, England. He didn’t join the military for any noble reason, but rather adventure. A naturally feisty personality and fiery temperament made him daring but also got him into trouble. He fought in the deserts of Egypt and Libya against the Italians and Rommel’s Africa Korps and was eventually captured by the Germans and became a prisoner of war. Avey, undeterred, made several desperate escape attempts, including a harrowing escape from a torpedoed ship that was transporting prisoners, only to be caught again. Avey was ultimately imprisoned long-term at the E715 POW camp at the IG Farben Buna-Werke complex which was also the location of the Auschwitz III-Monowitz concentration camp. The POW camp and Auschwitz III-Monowitz were so close together that their entrances were only 800 meters apart. In Avey’s words: “It was hell on earth…There was no grass, no greenery of any sort, just mud in winter, dust in summer.” During the day, the POWs, who were fed and treated better than the Jewish prisoners, were often forced to work alongside the Jews who were too weak to handle the heavy work that went on continually at the IG Farben complex.

As my friend Julian once told me, “war takes you totally out of everything. In a war, everything is turned upside down, nothing is the same anymore. Life is totally different. That’s why it haunts you and stays with you your whole life.” Avey gives his account with complete honesty. He shamefully recalls when Les, his friend and fellow soldier, was blown up next to him in the middle of a battle at Sidi Rezegh in Libya, his first thought was, “Thank God it wasn’t me.” He reveals all of his experiences in a transparent manner as well as his later struggle with post traumatic stress disorder and how it negatively affected his first marriage.

Who knows what each one of us would think or do in the same desperate circumstances that Avey experienced or in similar war conditions. The tragedy and indignity of war is such that, just to survive all the horrors, people are forced into shutting off emotionally and often reverting to the most primal state of self-preservation, which later thaws into post-traumatic stress disorder and crippling guilt. PTSD was even less acknowledged or understood than it is now. It was given the anemic term “combat fatigue” and generally swept under the rug as just another unfortunate consequence of war. In order to shield himself, Avey shut off emotionally and retreated deeply inward. For many years, he struggled alone with an especially severe case of PTSD. In his time, there were no adequate resources and he mainly dealt with it by not talking about it at all, because in his generation and culture, you just didn’t talk about experiences like that. It was only later in life, in speaking about and writing about his experiences, that he was able to experience some healing.

A number of times through his book, Avey, in describing how he handled himself in war conditions, states something along the lines of, “I had to think of number one,” or “I was just looking out for number one,” which I don’t feel is accurate. He was doing his best to survive some dismal and extreme circumstances, yet at the same time, he made a number of sacrifices and took risks where most people wouldn’t. There was little that was truly selfish on his part. This distortion and guilt is typical of people and veterans who survive extreme trauma and unspeakable horrors. Avey is obviously very hard on himself. Given what he witnessed, he probably feels he could and should have done more and was selfish, but the truth is, he was very courageous and self-sacrificing. He made a number of risks and effort when none was asked of him. He showed up for duty when he didn’t have to—he was given a plum assignment in South Africa and could have stayed there and lived the good life, but chose instead to go back to the deserts of North Africa to fight—which ultimately led to him being captured by the Germans. While imprisoned and working at the I.G. Farben complex, with the help of a civilian worker and using his engineering knowledge, he always made an effort to engage in some form of surreptitious sabotage in the complex. He also lost an eye after confronting an SS officer for beating a Jewish boy. And he did his best to give food to the jewish prisoners and make sure a jewish prisoner had extra cigarettes which were used like currency in the prison to obtain privileges and favors. These are just some examples of personal risk and sacrifice on the part of Avey. And finally the act that inspired the title of the book. The title makes it sound like he kicked down a door or snuck in through a window or something along those lines, but it was more like an “exchange” between Avey and a Jewish prisoner after he had developed a relationship of trust with him. I don’t want to be a spoiler and give too much away, so sorry, no more details—you’ll just have to buy the book.

There has been some controversy over whether Avey actually did enter Auschwitz. It is documented that he was a POW at the E715 POW camp, but no proof that he actually entered the Auschwitz camp, so there has been some speculation that in his old age, while not deliberately making up the story but through some form of wishful thinking, Avey had imagined this occurred, incorporating information about Auschwitz he gleaned over the years from other sources. Whether this is the case or not, isn’t that relevant to me. I don’t doubt he is doing his best to tell the truth. I spent countless hours with a World War II veteran, so sense when someone is telling the truth in regards to war. Avey’s descriptions of his experiences fighting in the desert campaigns of North Africa, as a prisoner, and as a fugitive on the run ring true. Even in the chance that he did “elaborate” on the Auschwitz portion, any mental confusion on his part would be something I would easily forgive, given his especially severe case of untreated PTSD. Besides that, for me, the quality of writing supersedes the controversy—it is a beautifully written book which in sections reads like a good thriller and worth a read just for that. A well-written book is always a pleasure to read.

Best of all, The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz has a thrilling surprise and message of hope at the end, complete with witnesses and proof. While it may have appeared to Avey that, in his words, “The Great Architect had turned his back on Auschwitz,” (I don’t agree with all of Avey’s thoughts and views, but that doesn’t mean I can’t like his book), the outcome of his story proves that there is hope even when things appear hopeless. I don’t want to give anything away, so I will make my point by just summarizing. Avey wrote some letters while a prisoner requesting something—this seemingly small and insignificant gesture bore fruit in an unexpected way that stretched across decades. When the BBC video taped Avey telling his story, they purposely placed him in front of a picture window with a view of Hope Valley in Derbyshire which immediately brought to my mind the Valley of Dry Bones in Ezekial 37 where the dry bones unexpectedly came to life. God breathed life into the valley full of dry bones and promised, “O my people, I am going to open your graves and bring you up from them: I will bring you back to the land of Israel.” What appeared to be completely dead, abandoned, and hopeless, there was still life in it. Even as flawed, muddled human beings, seemingly weak and powerless against overwhelming, dark forces, taking a risk—even in the form of a small act, a small gesture—can be like a breath of life and hope, as Avey proved with his actions.

When an Auschwitz survivor who was assisted by Avey was asked after telling his story what advice he would give future generations, he said: “For evil to succeed all that was needed was for the righteous to do nothing.” Both books make that important point, that we can’t be silent or passive. Reck, despite warnings from friends and Germany unleashing all of its demons, persisted in his writings. “Driven as I am by my own inner necessity,” he wrote, “I must ignore the warning and continue these notes.” If only more people would be driven by such an inner necessity—as Avey pointed out, the evil that came to full bloom and resulted in World War II can happen anywhere, at any time. In his words, “It could happen here. It could indeed happen anywhere where the veneer of civilization is allowed to wear off, or is torn off by ill will and destructive urges.”

(Posted 5/4/16)

I have been blessed to come across two striking first person, nonfiction accounts of that era: Diary of a Man in Despair by Friedrich Reck and The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz: A True Story of World War II by Denis Avey. I would recommend the books to anyone interested in learning more about that dark period in our history. I read the books last year since 2015 marked the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and even though that was many months ago, I thought back to the books often. The quality of writing in both books is especially notable, and the insights gleaned also serve as a warning on the current political climate.

“Eventually, he managed to launch into a speech. He talked on and on, endlessly. He preached. He went on at us like a division chaplain in the Army. We did not in the least contradict him, or venture to differ in any way, but he began to bellow at us. The servants thought we were being attacked, and rushed in to defend us.

When he had gone, we sat silently confused and not at all amused. There was a feeling of dismay, as when on a train you suddenly find you are sharing a compartment with a psychotic. We sat a long time and no one spoke. Finally, Clé stood up, opened one of the huge windows, and let the spring air, warm with the föhn, into the room. It was not that our grim guest had been unclean, and had fouled the room in the way that so often happens in a Bavarian village. But the fresh air helped to dispel the feeling of oppression. It was not that an unclean body had been in the room, but something else: the unclean essence of a monstrosity.

I used to ride at the Munich armoury, after which I liked to eat at the Löwenbräkeller: that was the second meeting. He did not need to worry now that he might be put out, and so he did not have to smack his boots continually with his riding whip, as he had done at Franckenstein’s. At first glance, the tightly clenched insecurity seemed to be gone—which allowed him to launch at once into one of his tirades. I had ridden hard, and was tremendously hungry, and wanted just to be let alone to eat in peace. Instead I had poured out over me every one of the political platitudes in his book. I know you will appreciate my sparing you, future reader, all the dogma. It was that little-man Machiavellianism by which German foreign policy became a series of legalised burglaries and the activity of its leaders a succession of embezzlements, forgeries, and treaty breaches, all designed to make him appeal to the assortment of schoolteachers, bureaucrats, and stenographers who have since become the true support and bastion of his regime . . .as a fabulous fellow, a real political Genghis Khan.

With his oily hair falling into his face as he ranted, he had the look of a man trying to seduce the cook. I got the impression of basic stupidity, the same kind of stupidity as that of his crony, Papen—the kind of stupidity which equates statesmanship with cheating at a horse trade.”

When he had gone, we sat silently confused and not at all amused. There was a feeling of dismay, as when on a train you suddenly find you are sharing a compartment with a psychotic. We sat a long time and no one spoke. Finally, Clé stood up, opened one of the huge windows, and let the spring air, warm with the föhn, into the room. It was not that our grim guest had been unclean, and had fouled the room in the way that so often happens in a Bavarian village. But the fresh air helped to dispel the feeling of oppression. It was not that an unclean body had been in the room, but something else: the unclean essence of a monstrosity.

I used to ride at the Munich armoury, after which I liked to eat at the Löwenbräkeller: that was the second meeting. He did not need to worry now that he might be put out, and so he did not have to smack his boots continually with his riding whip, as he had done at Franckenstein’s. At first glance, the tightly clenched insecurity seemed to be gone—which allowed him to launch at once into one of his tirades. I had ridden hard, and was tremendously hungry, and wanted just to be let alone to eat in peace. Instead I had poured out over me every one of the political platitudes in his book. I know you will appreciate my sparing you, future reader, all the dogma. It was that little-man Machiavellianism by which German foreign policy became a series of legalised burglaries and the activity of its leaders a succession of embezzlements, forgeries, and treaty breaches, all designed to make him appeal to the assortment of schoolteachers, bureaucrats, and stenographers who have since become the true support and bastion of his regime . . .as a fabulous fellow, a real political Genghis Khan.

With his oily hair falling into his face as he ranted, he had the look of a man trying to seduce the cook. I got the impression of basic stupidity, the same kind of stupidity as that of his crony, Papen—the kind of stupidity which equates statesmanship with cheating at a horse trade.”

Much later, at a public rally, in examining Hitler’s face through a pair of binoculars, Reck noted, “the face bore the stigma of sexual inadequacy, of the rancour of a half-man who had turned his fury at his impotence into brutalising others.” which is remarkable considering in recent years there has been some speculation, based on a doctor’s report, on Hitler suffering from a genital deformity. In reflecting on his impressions of Hitler over the years, Reck writes, “Notwithstanding his meteoric rise, there is absolutely nothing that has happened in the twenty years since I first saw him to make me change my first view of him. The fact remains that he was, and is, without the slightest self-awareness and pleasure in himself, that he basically hates himself, and that his opportunism, his immeasurable need for recognition, and his now-apocalyptic vanity are all based on one thing—a consuming drive to drown out the pain in his psyche, the trauma of a monstrosity.”

Reck also gives cutting observations on the social and economic forces in Germany that gave rise to Hitler and the Nazi war machinery. Hitler’s self-hatred and monomaniacal need for power coincided with a turbulent political and economic situation that had roots in previous regimes as well as the stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression. Add to this mix the German government’s increasing collusion with corporations and the relentless drive towards industrialization. Reck viewed the German fixation with mercantilism, industrialization, and technology as vulgar and barbaric, the mindset and mentality epitomized in what he derisively termed “mass-man”. Reck saw “mass-man” as spiritually bankrupt and ultimately spawned from the shadow side of the French Revolution which famously made Reason into a cult and germinated the concept and fervent hysteria of Nationalism “which puts an aura of heroism around mercantilism and the bourgeois drive for power…” In writing of this mass mentality that had become entrenched in Germany, Reck writes, “It was possible only at a time of generalised atheism, and purposelessness, and brute force. Of course, I.G. Farben welcomed Hitler—he provided their poison factory with the aura of a philosophy!” As if to validate the popular adage that Satan most successfully deceives by making people believe he (and God) doesn’t exist, in despair Reck writes, “My life is loneliness, and the growing awareness that it must be so—loneliness among a people whom Satan has overcome, and the awareness that only by suffering can the future be changed…” Reck further notes that Germany, in such a spiritually bankrupt atmosphere, gave license to its worst side: “every nation normally puts its demons, its delusions, its impossible desires away into the cellars and vaults and underground prisons of its unconscious; the Germans have reversed the process, and have let them loose.” As we all know, all these forces and elements plaguing German society came together as in a perfect storm culminating in the Nazi military industrial complex and a military campaign bent on taking over all of Europe as well as its most evil manifestation—industrialized murder.

As my friend Julian once told me, “war takes you totally out of everything. In a war, everything is turned upside down, nothing is the same anymore. Life is totally different. That’s why it haunts you and stays with you your whole life.” Avey gives his account with complete honesty. He shamefully recalls when Les, his friend and fellow soldier, was blown up next to him in the middle of a battle at Sidi Rezegh in Libya, his first thought was, “Thank God it wasn’t me.” He reveals all of his experiences in a transparent manner as well as his later struggle with post traumatic stress disorder and how it negatively affected his first marriage.

Who knows what each one of us would think or do in the same desperate circumstances that Avey experienced or in similar war conditions. The tragedy and indignity of war is such that, just to survive all the horrors, people are forced into shutting off emotionally and often reverting to the most primal state of self-preservation, which later thaws into post-traumatic stress disorder and crippling guilt. PTSD was even less acknowledged or understood than it is now. It was given the anemic term “combat fatigue” and generally swept under the rug as just another unfortunate consequence of war. In order to shield himself, Avey shut off emotionally and retreated deeply inward. For many years, he struggled alone with an especially severe case of PTSD. In his time, there were no adequate resources and he mainly dealt with it by not talking about it at all, because in his generation and culture, you just didn’t talk about experiences like that. It was only later in life, in speaking about and writing about his experiences, that he was able to experience some healing.

A number of times through his book, Avey, in describing how he handled himself in war conditions, states something along the lines of, “I had to think of number one,” or “I was just looking out for number one,” which I don’t feel is accurate. He was doing his best to survive some dismal and extreme circumstances, yet at the same time, he made a number of sacrifices and took risks where most people wouldn’t. There was little that was truly selfish on his part. This distortion and guilt is typical of people and veterans who survive extreme trauma and unspeakable horrors. Avey is obviously very hard on himself. Given what he witnessed, he probably feels he could and should have done more and was selfish, but the truth is, he was very courageous and self-sacrificing. He made a number of risks and effort when none was asked of him. He showed up for duty when he didn’t have to—he was given a plum assignment in South Africa and could have stayed there and lived the good life, but chose instead to go back to the deserts of North Africa to fight—which ultimately led to him being captured by the Germans. While imprisoned and working at the I.G. Farben complex, with the help of a civilian worker and using his engineering knowledge, he always made an effort to engage in some form of surreptitious sabotage in the complex. He also lost an eye after confronting an SS officer for beating a Jewish boy. And he did his best to give food to the jewish prisoners and make sure a jewish prisoner had extra cigarettes which were used like currency in the prison to obtain privileges and favors. These are just some examples of personal risk and sacrifice on the part of Avey. And finally the act that inspired the title of the book. The title makes it sound like he kicked down a door or snuck in through a window or something along those lines, but it was more like an “exchange” between Avey and a Jewish prisoner after he had developed a relationship of trust with him. I don’t want to be a spoiler and give too much away, so sorry, no more details—you’ll just have to buy the book.

There has been some controversy over whether Avey actually did enter Auschwitz. It is documented that he was a POW at the E715 POW camp, but no proof that he actually entered the Auschwitz camp, so there has been some speculation that in his old age, while not deliberately making up the story but through some form of wishful thinking, Avey had imagined this occurred, incorporating information about Auschwitz he gleaned over the years from other sources. Whether this is the case or not, isn’t that relevant to me. I don’t doubt he is doing his best to tell the truth. I spent countless hours with a World War II veteran, so sense when someone is telling the truth in regards to war. Avey’s descriptions of his experiences fighting in the desert campaigns of North Africa, as a prisoner, and as a fugitive on the run ring true. Even in the chance that he did “elaborate” on the Auschwitz portion, any mental confusion on his part would be something I would easily forgive, given his especially severe case of untreated PTSD. Besides that, for me, the quality of writing supersedes the controversy—it is a beautifully written book which in sections reads like a good thriller and worth a read just for that. A well-written book is always a pleasure to read.

Best of all, The Man Who Broke Into Auschwitz has a thrilling surprise and message of hope at the end, complete with witnesses and proof. While it may have appeared to Avey that, in his words, “The Great Architect had turned his back on Auschwitz,” (I don’t agree with all of Avey’s thoughts and views, but that doesn’t mean I can’t like his book), the outcome of his story proves that there is hope even when things appear hopeless. I don’t want to give anything away, so I will make my point by just summarizing. Avey wrote some letters while a prisoner requesting something—this seemingly small and insignificant gesture bore fruit in an unexpected way that stretched across decades. When the BBC video taped Avey telling his story, they purposely placed him in front of a picture window with a view of Hope Valley in Derbyshire which immediately brought to my mind the Valley of Dry Bones in Ezekial 37 where the dry bones unexpectedly came to life. God breathed life into the valley full of dry bones and promised, “O my people, I am going to open your graves and bring you up from them: I will bring you back to the land of Israel.” What appeared to be completely dead, abandoned, and hopeless, there was still life in it. Even as flawed, muddled human beings, seemingly weak and powerless against overwhelming, dark forces, taking a risk—even in the form of a small act, a small gesture—can be like a breath of life and hope, as Avey proved with his actions.

When an Auschwitz survivor who was assisted by Avey was asked after telling his story what advice he would give future generations, he said: “For evil to succeed all that was needed was for the righteous to do nothing.” Both books make that important point, that we can’t be silent or passive. Reck, despite warnings from friends and Germany unleashing all of its demons, persisted in his writings. “Driven as I am by my own inner necessity,” he wrote, “I must ignore the warning and continue these notes.” If only more people would be driven by such an inner necessity—as Avey pointed out, the evil that came to full bloom and resulted in World War II can happen anywhere, at any time. In his words, “It could happen here. It could indeed happen anywhere where the veneer of civilization is allowed to wear off, or is torn off by ill will and destructive urges.”

(Posted 5/4/16)